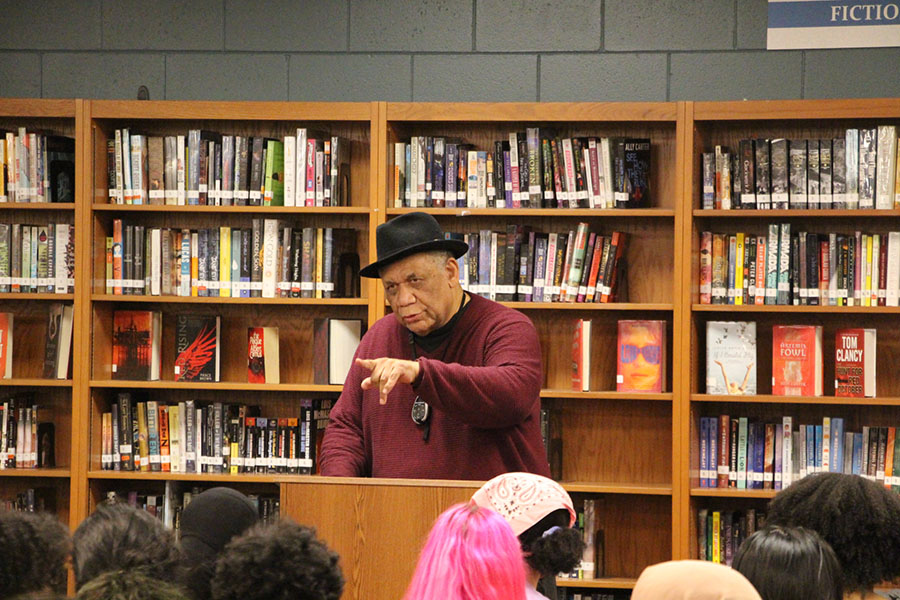

Black and red: SMASH and BSU host communist speaker Frank Chapman

Last Friday, the Student Marxist Association of South High (SMASH) and the Black Student Union (BSU) hosted Frank Chapman, a black communist activist and former political prisoner who has worked with both the Black Panthers and the Communist Party USA.

February 14, 2020

Last Friday, the Student Marxist Association of South High (SMASH) and the Black Student Union (BSU) hosted Frank Chapman, a black communist activist and former political prisoner who has worked with both the Black Panthers and the Communist Party USA.

Chapman addressed a significantly large group of students (approximately 50), mainly regarding the interconnectedness of Marxism and the struggle for civil rights. Chapman explained that to be Communist was to be inherently pro-black liberation.

“Labor cannot be free in the white skin while branded in the black skin,” Chapman reiterated to attendees throughout his discourse, illustrating the obvious contradiction of society pushing for socialism while also oppressing others.

Chapman was first imprisoned (wrongfully) at age 18 in 1961 to life and 50 years for armed robbery and murder. During this time he was first introduced to communism through fellow inmates, and became enthralled by the works of Karl Marx, Angela Davis, and other marxist writers.

While in the Missouri prison, Chapman and his comrades became increasingly aware of the racial disparities and growing tensions.

“Once I got in there, I saw that the black people in there were being treated way worse than white prisoners. We were all convicts, but they had all the black prisoners herded up into one cell block. In the cell block they had us herded up into, there was six men to a cell. White guys had a cell block of one and two man cells.”

The lunchroom at the prison was divided amongst the white and black inmates, and an invisible line splitting the room in half. Prisoners new not to break that boundary. Tensions plateaued when someone crossed that line. A child.

The child was then beaten, and a fight ensued. Not only a physical fight: a massive lunchroom brawl, but the fight for equality within the prison.

“We started protesting. We started fighting for better living conditions and better working conditions. We were stacked on top of each other in the cell block. The working conditions were [that] they gave the most dangerous jobs to [black prisoners].”

One of the more dangerous jobs, which was (unofficially) reserved for black prisoners was license plate stamping. The embosser, the machine that presses the numbers onto the plate, often resulted in inmates losing fingers. The prison compensated the prisoner with $20 per month for the rest of your sentence.

1973 Chapman’s case was taken up by the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression (NAARPR). He was released just 3 years later, after serving 14 years behind bars. He continued working with NAARPR after he was free, and was elected the executive director.

Chapman works as a writer, and has written multiple books, about his experience as a prisoner and as a communist of color, all of which are available on Amazon. Frank is currently the co-chair of the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression.

![A power outage on Friday May 12 before the start of the school day led many students to leave the building and miss parts of first, second and third hour. “[Staff at the front door] said the power might be on at 11, so [we should] come back to school at 11,” recalled freshman Riley Olson. “A lot of people went back home.” However, Principal Afolabi Runsewe claimed and maintains that students were told to stay in the commons and were never given the option to leave school.](https://www.shsoutherner.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/power-outage-475x356.png)