Reading between the redlines: Minneapolis’ hidden history of denied housing

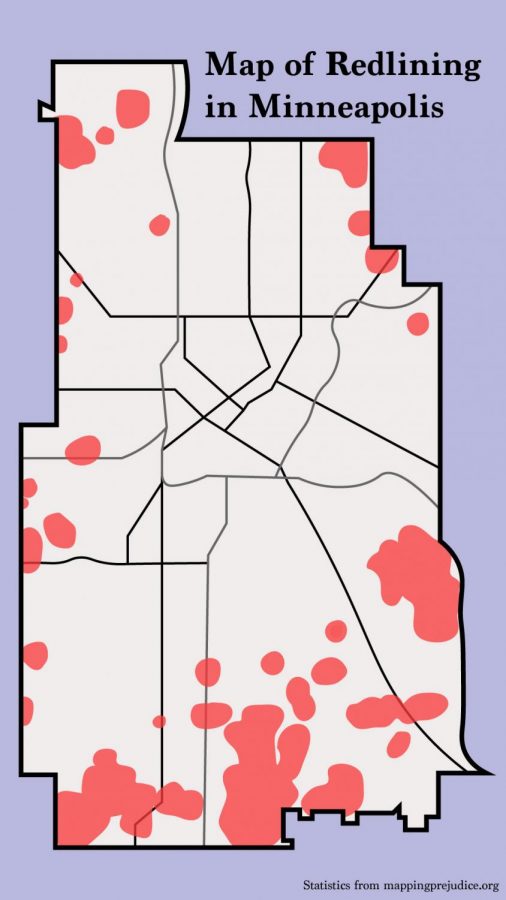

An Augsburg college study done in 2014 recorded every known instance of redlining within Minneapolis and placed them on a map of the city as a red dot. As they went through year by year of reports (from 1911-1951) the dots became blots that covered entire districts. This was what their map looked like in 1951.

In 1947 the law was changed that prohibited racial covenants from being used in neighborhood developments in Minneapolis. This meant that legally, no limitations could be put on what race could inhabit any specific neighborhood. The government could not deny housing to ethnic minorities because of their race.

Now, 60 years after that law has been abolished, segregation can still be seen throughout the city. People of color are denied housing and services, and there is an obvious difference in distribution of resources and wealth between people of color and white people. The segregation of domain was made illegal, yet it still remains.

North Minneapolis has a population of 70% non-white races, according to data from the 2010 U.S. census, which is astronomical considering white people make up 60% of Minneapolis’ total population. This clearly demonstrates the huge difference in diversification of Minneapolis’ neighborhoods.

Holiday Samabaly, English teacher, Dare 2 B Real advisor, and one of the few staff members of color at South speaks about some examples of modern day segregation: “[In] schools, neighborhoods, access. [Redlining] isn’t overt or forthright.” Redlining is the term for denying services to people in certain areas based on the racial or ethnic composition of that area.

“I know that right now, in North Minneapolis they’ve proposed that it should be a historical district of mostly Jewish history,” said Samabally. In the 19th century North Minneapolis became a safe haven for Jews and people of Jewish descent. It was a community where they could be with people of the same background and status, as a means to escape the anti-semitism they faced in their previous residences.

The first wave of Jewish immigration to the US consisted of 250,000 German Jews from all over central Europe, 1,000 of them came to Minnesota. From 1882 to 1924 a wave of more than 2 million Yiddish Jews immigrated to America, approximately 20,000 of whom settled in Minnesota.

As anti-semitism was still a strong factor in America’s social environments, the Jewish community of the north side was strongly discriminated against and denied housing in any other areas outside of their local community.

“Racism can play out in very different ways,” Samabally said. “For one, the people who stayed in that community are not being honored I feel. Two, what making something a historical district does to the value of the homes. Resale value, trying to sell, that can also be super harmful. While think it’s important that we are paying homage to the people who built the homes or the neighborhood, I still think it can be really hurtful for the people who inherited that neighborhood,” Samabally said.

A project was created in 2014 at Augsburg college called Mapping Prejudice, whose goal was just that; to map all incidents of people of color being denied housing by landlords for the color of their skin. Their studies showed that redlining occured heavily in many neighborhoods throughout southside Minneapolis, including: Longfellow, Seward, Cooper, Regina, Hale, Northrop, Field, Page, Diamond Lake, Armitage, Fulton, Lynnhurst, and various other neighborhoods throughout the city. The earliest accounts of redlining revealed in the project were in 1911, but grew onwards to 1954, which was almost a decade after it was declared illegal to segregate housing. It seemed that there was little the government or anyone else could do about it. Home owners could sell their house to whoever they want to.

“There’s a difference between ‘de jure,’ which is the legal [segregation], and ‘de facto’ which was the way [segregation] was. There’s all kind of things that are illegal which still happen.” said Human Geography teacher Richard Nohel.

De Facto is essentially just another term for redlining. Individuals who aren’t connected to the government refusing housing to people of color. De Jure is the type of segregation seen in Jim Crow, where the government legally segregated people.

“The government can’t [legally segregate], but landlords can. People can sell their house to whoever they want. And that’s the thing is that when this ‘block-busting’ occured,” (block-busting is when people buy houses for cheap and sell them at high value to people of color) said Nohel, “Sometimes there were white people who were pressured to sell their house by their neighbors to under no circumstance sell their houses to a person of color. And people either went along with it, or if they didn’t, within a certain number of months after they moved in everyone in the neighborhood would move out.”

But years passed and laws were created which allowed other cultures to integrate into and out of different communities and diversify neighborhoods. Minneapolis slowly became more and more of a “salad bowl” (which is a term for a community that is considered to be a mix of cultures and ethnicity), yet there is such a drastic difference of access and resources in ethnic neighborhoods and communities.

“After Civil Rights segregation became more systematic than the ‘in your face’ oppression there had been,” said Junior Elise Cuff, “[an example is] how schools are all different. I went to Lake Harriet when I was in middle school, which was mostly white kids. In the whole school there was about five or six black kids (including myself). And then Nellie Stone Johnson, which I went to in 6th grade, which was almost entirely black or Latino kids.”

Samabally believes that the greatest threat about segregating schools are the resources within them. “I more so see [an issue with] the funding. It’s not even between neighborhoods. I look at a school like [South]… I’ve been in schools like Fair, and Southwest, and I see inequalities. There isn’t really an equal distribution of funds. At all.”

So how do we solve this problem? Besides time, effort and strides toward equality, redlining isn’t something most people can solve on their own. As Samabally said, “There is a fear of ‘if I go into this neighborhood what is going to happen to me?’ What are the real life consequences [of trying to integrate]? It is a very real fear and when we think about anxiety and people of color having health issues related to ‘racial anxiety’ and all of that, you think ‘is it worth it?”

“I think we can solve [redlining] by coming together as a whole community, over all of Minneapolis,” said 11th grader Jewel Ferguson, “Minneapolis is very divided by neighborhoods like Corcoran and Powderhorn and Seward. I think the whole problem here is that we need to start viewing ourselves as one.”

Tannen Holt is a senior and is back for his third year on the Southerner. He is excited to be on staff again after taking a year off from the newspaper....

Eli Shimanski, a senior, is ready as ever for this year, as long as he’s always listening to the album Views by Drake. Our very own visual media editor...