Casual racism and the model minority myth: why schools must better serve Asian students

Casual racism, the model minority stereotype, and an overall lack of support in school is troubling to Asian American students.

May 3, 2022

I believe the Asian American experience in school cannot be defined by one encounter. My personal stories and analysis of school could be completely different from other Asian Americans. Each experience is made unique by where in America you live, what part of Asia your family is from, and what generation of American you are. Our diaspora in the states is as vast as it is back in Asia, and I think that is important to remember as you read this single interpretation of the Asian American experience in school.

I went to Clara Barton Open for elementary school. I was one of (at the most) ten Asian kids in the 500-student K-5 program, and I was related to two of that small group. When I was little, I wanted to fit in so I never mentioned that I was Asian until I became a middle schooler. Looking back on my youthful thinking, I realize how wrong this was. So why did I decide this was the path to take? I believe that it is because I never felt supported or accepted as an Asian student at school. No person should feel like they need to hide such a massive part of their identity just to assimilate to a more dominant culture, but being in the minority can often suppress our true selves.

Now as a senior in high school, I am much more involved with my Asian identity. Sadly but not regrettably, this has come at the cost of experiencing several uncomfortable and harmful moments because of my race throughout my time at South. I’ve been called a “North Korean spy,” and I’ve heard racial slurs in school on several occasions. I’ve had people exoticize my culture and wrinkle their noses any time I’ve brought something remotely “ethnic” to school. I’ve also simultaneously experienced the fetishization and appropriation of my culture. I’ve seen people wear traditional Asian clothes they thrifted, wear shirts with Asian languages on them that they don’t understand, and talk about how they love Panda Express’s (VERY authentic) orange chicken. Overall, it has been kind of brutal.

In the classroom specifically, I’ve never had a teacher hold a class discussion about issues affecting Asian Americans. This is paralleled by countless discussions about mental health and watered-down racial justice. I’ve had a teacher at South essentially call me white-passing to invalidate my racial background. This is just a sample of the microaggressions that I have experienced at this school.

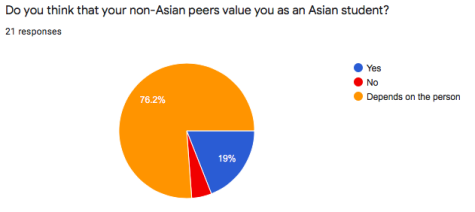

I am not alone in these experiences. According to a survey given to about half the members of the Asian student body by the Southerner, 52% of Asian students surveyed have been the victim of a racist encounter in school. Only 29% said they think admin does enough to support Asian students and only 33% said the same for teachers. Overall, just 19% of Asian students surveyed feel supported by their peers. This reflects both the casual and systemic racism Asian Americans face in schools.

Casual Racism is prominent in our schools

Casual racism is especially seen in majority-white, Minnesota high schools. “I think that every single Asian American student that goes to a predominantly white high school has experienced some form of racism, and even if you haven’t experienced it to your face people are often making fun of you behind your back,” said Edina High School senior Louisa Darr. Oftentimes, the racism Asian American students face only scratches the surface of what unfiltered comments their peers say about them. Casual racism affects us even when we aren’t paying attention.

One recent example of hidden casual racism that has plagued Minnesota schools is the racist and anti-semitic video that surfaced out of Edina High School last month. A group of Edina students posted a Snapchat video in which they mocked Asian accents and performed the Nazi salute. Part of the video is illegible, so we don’t even know what the group said before the sound focused. This incident sparked outrage in Minnesota’s Asian and Jewish communities and even got coverage from the local news. This incident prompted the question: If this is what these kids feel comfortable saying on camera, what do they say when they aren’t being recorded?

For Darr, this was one of the questions she asked herself after watching her classmates’ horrific video. “I [was] coming down from the show I was doing at Theater Mu, which is the nation’s 2nd largest Asian American theater company… I got a text from my sister, and she said, ‘have you seen the video?’ I [responded with], ‘What video?’ She sent me the link and I watched it and my jaw just dropped. I knew all the kids in this video, the words they said were disgusting, and it was overall numbness and shock for like a good 5 minutes,” she said.

Darr ended up being interviewed by the Star Tribune and appearing on WCCO, amongst other outlets. She credits Theater Mu for connecting her with the press; she doesn’t think that the incident would have received the same attention without the company’s help. Darr’s Star Tribune interview was even used by Nextshark, a leading source of Asian American news. Darr said she hoped to be on Nextshark someday as an accomplished actor, not for speaking out about a racist video.

Edina Public School officials sent out messages in response to the incident, including principal Andy Beaton. “The nature of the post is culturally insensitive and violates our core values. We responded immediately, investigated and took appropriate action in alignment with district policy and protocols,” Beaton wrote. Due to legal reasons, the school could not disclose what disciplinary action was taken. However, Darr believes that the punishment was not enough and that she thinks an appropriate penalty would have been at least a suspension. Edina also had a student government forum open to students to talk about the incident. This upset many students, including Darr who wanted a school-wide discussion instead. The response of the administration sparked a walkout at the school, adding to an already frustrating situation.

This example clearly demonstrates both the casual and systemic racism that is prevalent in Minnesota schools. Casual racism in the video, systemic racism in the lack of action from Edina High School, and the supposed underwhelming penalty the students faced.

What is the model minority myth? How does it contribute to systemic racism?

Perhaps the root of this inaction can be traced back to the model minority myth. Created by a white sociologist in the 1960’s, the model minority myth assumes that Asian Americans, despite the barriers they have faced in the US, have now “made it” and thus are the “model” for how other minority groups should act. This stereotype assumes that Asian Americans are quiet, obedient, and studious individuals. This stereotype is harmful to Asian Americans and other racial minorities because it pits everyone against each other. It is also harmful to Asian Americans who don’t fit the stereotype. “It puts a lot of pressure [on us]… It’s just kind of difficult to have a stereotype put on you and you don’t fit the stereotype,” said senior Zoe Riordan.

This can be applied to the Edina High School situation because the model minority myth also assumes that Asian Americans don’t face discrimination. This assumption helped the school’s administration get away with what was in my opinion an underwhelming response to the incident. Clearly, the school buys into the model minority stereotype because if they thought otherwise they would have done more to support their students following the event. The myth invalidates any systemic oppression and harm Asian Americans face, and we can clearly see that in this example.

Sadly for South High School, it seems we buy into the model minority myth as well. 52% of the Southerner’s survey respondents said they think they have teachers who believe in the model minority myth. Additionally, 76% of respondees said they think that their peers don’t believe that Asian Americans face systemic discrimination in schools. These two data points directly align with the model minority myth, exposing a need for change at our school.

South High School’s lack of response following the Atlanta Shooting

Similar to the model minority myth, another way the school and district administration perpetuates harm against Asian Americans is through their lack of communication during traumatic events affecting Asian Americans. Last year, Asian America was rocked when a gunman killed eight people in three separate spas near Atlanta, Georgia. Six of the victims were Asian women. Despite the magnitude of this event, Minneapolis Public Schools showed no support for its Asian American students. We see this not only with Asian students, but with the treatment of other students of color as well. Barely anything has been done to respond to police brutality targeting black and brown people. Little to nothing has been done to address missing and murdered Indigenous women. Furthermore, throughout the pandemic, there were no messages condemning Anti-Asian hate from the district and no conversations in classrooms about the rise of hate crimes/incidents against Asian Americans. While this wasn’t surprising, for I feel that Asian Americans have never been prioritized or seen in school, it still was heartbreaking.

South’s Asian staff put together a video about the Atlanta shooting in support of their Asian students. However, even that almost didn’t happen when it became apparent that the administration wasn’t planning on addressing the event. The video itself was powerful because I know South’s Asian staff cares about me and made me feel supported. However, the admin’s lack of action felt like a slap in the face. “All around, the district needs to work on acknowledging how marginalized communities are affected by incidents that happen, even if they are across the country like the Atlanta shooting,” said English teacher Irene Mineoi-Amrani.

Solutions

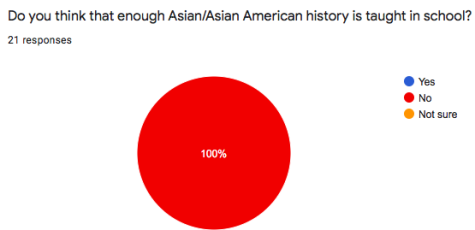

The best and easiest way to increase support for Asian American students is through representation in the curriculum. Every single student who took the Southerner’s survey said that not enough Asian history is taught in school. Every single one. Briefly (if at all) learning about the Chinese Exclusion Act and Japanese Internment during WWII is not enough to tell the story of Asian America. Curriculum should also expand from only talking about Asian suffrage and explore more positive points in Asian American history.

We also need to understand that Asia is not just China, Korea, and Japan. “We first need to acknowledge that South Asia [amongst other parts] is part of Asia [too], and work on getting that representation out there, more than just East Asia… I [also] think they find [that] any Asian issues… are just a second choice to [other topics in class]… I think it is equally important to teach all parts of the history of America… all races, all ethnicities,” said sophomore Aisha Abdullah.

South also needs to appreciate its Asian staff more. “I don’t feel valued, and I don’t know if that’s because of my intersecting identities or that I’m more soft-spoken and not as aggressive as someone else in a meeting, but I’m learning to advocate for students better and use my voice in a stronger way,” said Mineoi-Amrani.

Obviously, there is a long way to go before Asian students and other students of color feel valued in school. There is a lot to work on, but I believe that this can be slowly obtained with the effort we lack now. Let us not sweep Asian American history and issues under the rug anymore. Let us stop normalizing casual racism. Let us eliminate the model minority myth so that all those affected by it can band together and fight a common fight. I may feel that my education as an Asian student has been negative and stunted, but I am hopeful that someday with the effort I seek, schools will make a wonderful place for kids like me.

Lasai • Mar 13, 2023 at 10:03 am

Wow thanks for this incredible article!