All Nations students connect with culture in buffalo hunt

So far the skull has been decorated, the hide removed, some of the meat prepared and turned into chili, tacos, and jerky, and the teeth and bones removed for later decorative use. When spring comes, students will continue learning traditional practices and techniques such as tanning the buffalo hide.

The buffalo is historically the center of life for the Lakota people. Their food, tools, clothing, homes and ways of life revolved around the animal. The buffalo or tatanka, (the Lakota word for the animal,) was an important and sacred resource for the Lakota people.

The mass killing of buffalo as a weapon against Native people in the colonial era played a role in stripping them of their culture and makes the generations old tradition of a buffalo hunt all the more important. Only in the last half a century have the buffalo made the slow rise in population. Still though, the numbers are nowhere near where they used to be, according to Vince Patton, a social studies teacher in South’s All Nations program and organizer of the hunt.

Lakota people don’t rely on the buffalo as a primary means of survival anymore, but the hunt still continues as an important tradition that connects them to their ancestors. Sophomore Joseph Santana said, “it was really important for us young Native men to see what our ancestors used to do and how its still being carried on.”

This past November three students from South’s All Nations program took a trip to the Pine Ridge Reservation, located in South Dakota, and took part in their first buffalo hunt. The students there were sophomores Joseph Santana and Travis Lumbar and junior Clifton Hallow. The trip’s main focus was to connect the students with their culture and traditions to help their futures as students and community members.

On the day of the hunt the sky was cloudy and wind carried occasional light gusts of snow. The students, South staff, Patton’s family, and community members bundled up in cold weather clothes. Despite the weather, excitement and anticipation ran high. “It was very cold but exciting because this is the first time I’ve ever been to [a buffalo hunt,]” said Santana.

Before the hunt took place the people present performed the ceremonies that are a part of paying respects and honoring the tradition of what was about to be done. Hallow said, “there’s certain things you do before the buffalo [hunt] like praying and singing certain songs for it, for its journey.” It was requested that the specifics of these ceremonies not be included in the article as some things are sacred and meant to remain within the the Native community.

This was Patton’s first buffalo hunt and his telling of the story shows how sacred this tradition is and the power of the Native people’s connection to the animal. As Patton said, “when your doing something sacred, sacred things happen.”

Patton started the story with the moment of the kill shot, “I shot it and I didn’t quite hit it exactly where I needed to drop it. So we had to wait and that buffalo started suffering. He was hurting. I blew out his leg, so the buffalo is sitting there [on] one leg panting and the blood’s starting to come down his face and all the sudden he just falls, lays down.”

Patton continued, “when that happened about 20 other buffalo came up to that buffalo and tried to pick him up. Two or three first came by, lifted their horns under his butt trying to lift this buffalo up and another one comes around front trying to lift him up. [They] surrounded him in a big circle trying to [say] ‘get up, get up get up’ [but] that buffalo just couldn’t do it,”

“Eventually the whole herd – about 45 in that pasture – came by and they all circled this buffalo and they started walking in a big circle and that buffalo was dying there, laying there, sitting there, still cognitive, head up breathing hard. Those buffalo danced in a circle and one by one after they went around they started walking away. They just walked away, all in a straight line and they said ‘travel well.’ That was one of the hardest things for me, I cried,” said Patton, as his voice dropped lower.

All of the people interviewed described how moving it was. Hollows said, “I felt [a] very strong connection because as soon as Patton shot the buffalo every other male buffalo surrounded him saying their goodbyes.” Patton also said, “it just blows my mind and it reminded me of why our Lakota do what we do.”

After the buffalo was down the people on the hunt performed the traditional ceremonies to honor and thank the animal for its life and began to process of preparing the animal to be moved. A full grown buffalo weighs roughly 600 pounds and requires a lot of work to cut into manageable pieces.

This trip seemed to accomplish in giving the students what Ray Aponte, principal of South High and Patton were hoping for. Santana said, “all of us really valued our time up there and it helped us stay focused.”

When the buffalo was moved back to South High students from All Nations, and some from the Liberal Arts and Open programs, began the process of putting every part of it to use. So far the skull has been decorated, the hide removed, some of the meat prepared and turned into chili, tacos, and jerky and the teeth and bones removed for later decorative use. When spring comes, students will continue learning traditional practices and techniques such as tanning the buffalo hide.

South sophomores Joseph Santana and Travis Lumbar, and junior Clifton Hollows recently took part in a buffalo hunt on the Pine Ridge Reservation. The buffalo or Tatanka, the Lakota word for the animal, is a sacred animal to the Lakota people. The tradition of the buffalo hunt is one that spans generations and is a significant right of passage that hasn’t been possible for the last half a century because of the near extinction the animal faced from colonial attempts to destroy native cultures. Now that the species has made a gradual regrowth, reservation members are able to take part in the tradition once again. Photo courtesy of Ray Aponte

A Lakota man’s first buffalo hunt is an extremely important right of passage and because of the near extinction during the 19th century, many have not gotten the chance to experience it. “The buffalo was always out of our reach. Nobody in our family has gotten a buffalo before,” said Patton.

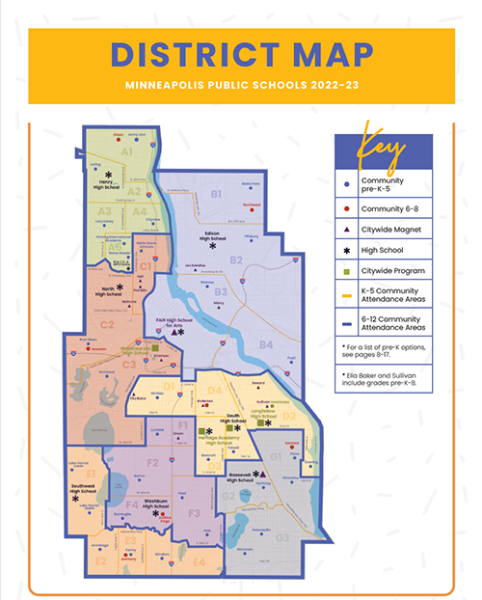

Patton is a member of the Pine Ridge Reservation, where the hunt took place. Pine Ridge like many Native reservations faces issues of poverty, substance abuse, homelessness, low graduation rates, and other issues. “The issues we see on the reservation can be summed up into one really big idea and it’s called historical trauma,” said Patton.

Historical trauma is “when certain historical events [happen to] a certain population -for example the Lakota people and Wounded Knee- [the] whole group will suffer from that and that gets carried with them,” said Patton. This trauma gets passed through generations and is sometimes referred to as a “Blood Memory.”

These struggles that Native people face continue to be an issue across the country including outside of the reservations.

According to Aponte, Native students continue to have the lowest graduation rates compared to other groups at South. Aponte says that since he’s been here, “every other population has made [gains] in regards to graduation rates. African American kids have gained, East Africans [have] gained, Latino kids [have] gained, but the Native population continues to flatline on me.”

Aponte is looking to make more of these out of school experiential activities possible for the Native students. He said, “I’m losing my people, I’m losing the Native kids to everything out here and so by doing these I’m hoping that it builds a little resilience and grit in who they are as people.” He plans to organize trips to the Black hills and Widjiwagan as well as make the buffalo hunt a yearly event.

“Having the buffalo back is one step going forward to heal this historical trauma that people experienced,” said Patton. He believes that by continuing to make experiences like this possible for native students, this healing process will continue. Patton said, “as long as they develop their identity and they stay connected to their culture I know that this will stick with them forever.”

Talula Cedar-James has a knack for tinkering with problems until they work. She is putting this skill to good use this year as she enters her second year...

Arden Santana • Feb 16, 2019 at 2:05 pm

I am grateful and most thankful to all the staff and all others who made the trip possible. I’m sure my son Joseph learned alot about our Lakota Culture and will carry that knowledge with him always.

Sincerely,

Arden Santana