Microaggressions: the effects of subconscious biases

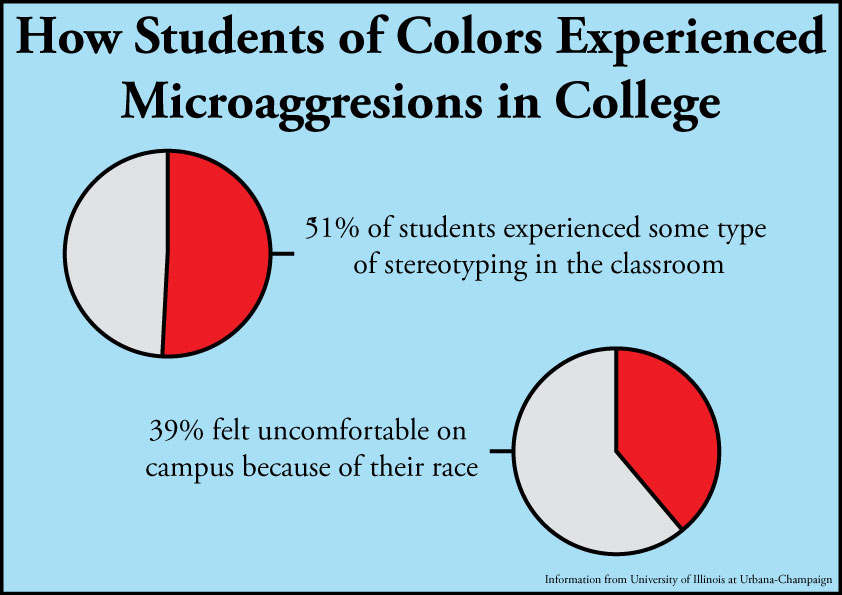

Above is an infographic showing the percent of college students who feel affected by microaggressive behavior and who feel as if their race makes them uncomfortable on campus. This research is according to a study done by the University of Illinois.

May 7, 2018

When asked about microaggressions, many people do not know what is meant by the term, and are unsure whether they have even experienced them or not. “Microaggressions are a sub-branch from general oppression; it’s everyday things that are a result of societal issues that are kind of hard to point out,” said Senior Viola Onikoro-Arkell.

Merriam-weber dictionary defines a microaggression as, “a comment or action that subtly and often unconsciously or unintentionally expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a marginalized group (such as a racial minority).” Furthermore, Psychology Today explains that micro-aggressions can be, “verbal, nonverbal, and environmental snubs,” which can be intentional but don’t have to be.

There are a variety of ways that microaggressions manifest, all of which can be very impactful on the person who they’re directed at. Within South’s student body, microaggressions are common from peers. However, they’re not always perceived by the people around them, or even by the person who spoke offensively. “It’s hard to pinpoint why it’s offensive or problematic because it’s a little more underground,” Onikoro-Arkell said.

To bring more awareness about microaggressions, there was recently a microaggressions course taught at South by New York University professor Lisa Arrista for a week. Most participants say they were informed of the opportunity by math teacher Stephanie Woldum. The project was taught by Professor Lisa Arrista.

The project went for roughly a week, consisting of vigorous workshops that condensed the broad college curriculum on the topic into a week long course. “We didn’t get any credits. It was basically just an intensive workshop; in four days they crammed in like fifteen weeks worth of curriculum,” said Junior Sofia Haase-Oliva. “They’re working on making it so that students get credits through New York University, I would recommend it to people next year.”

The final outcome of the course was student-created projects that consisted of short recorded verbal essays on the concept of microaggressions. For freshman Deisy Cervantes, this was an opportunity to “speak for others and problems that other people don’t really understand, and how it affects us as a community.”

Haase-Oliva focused her project on microaggressions shown towards women. “[Lily Comer talked about how] as a woman, she felt as if women were very dragged out and that the world saw women, specifically youth, as powerless,” she said.

Other examples of micro-aggressions include people at a restaurant getting less attention than other customers, or people in hospitals not being treated as quickly or as effectively as other patients.

Onikoro-Arkell discussed her experiences with microaggressions at South. “In the hallways I get stopped for passes often, and the funny thing is that I get stopped for passes more when I am with other people of color, but if I’m with white people then I don’t get stopped. Also, if I’m with guys I’ll most likely be stopped more often than if I’m with other ladies.”

Freshman Bella McQuerry shared that she has experienced microaggressions from people within the same minority groups as her own. “[If] I share a ‘race’ with people who will be microaggressive towards me, I’ll tell them and they’ll just laugh it off because they don’t think it’s a thing, especially because we share a skin tone or something,” McQuerry said.

McQuerry stated that in her experiences, “if the person is of an opposite skin tone, they’re more likely to say they’ll stop it.” She continued to describe several microaggressions she has experienced: “A very popular one, especially with cultural minorities, is people touching our hair… Another one is people making comments about my appearance, especially based on my ethnicity.”

When discussing microaggressions, the misconception that racist and sexist acts are the only aggressions is common. Therefore, most people don’t get called out for other offensive acts. “I don’t think people are commonly called out for cis-normative language, for classist things, or ableist things,” Onikoro-Arkell pointed out.

If you see or experience a microaggression either directed at a peer or at yourself, it can be difficult to bring outside attention to the issue. “It’s really tiring to call people out; you have to explain yourself. It’s hard, but in terms of doing it, I think you have to have the courage to say ‘this happened, and this is not okay because…’ or ‘I am offended by that because…” said Onikoro-Arkell.

“If microaggressions are happening towards you and you feel uncomfortable with [them], if you have the confidence to speak up, then definitely speak up for yourself,” McQuerry said. However, because calling people out can be such an uncomfortable experience, McQuerry also recommends reaching out to a trusted individual if you are not confident addressing the issue on your own.

“It’s really hard because… especially at south there is such a culture of being ‘liberal’ and ‘woke’ that if you make one mistake you’re outcast forever, so it’s hard to have actual, constructive discussion about it,” Onikoro-Arkell continued.

Furthermore, it is important to keep in mind that microaggressions are typically defined as subconscious acts, and since they can vary between a broad variety of topics, most people will end up being microaggressive at one point or another. “[Microaggressions are] heavily influenced by society; your perception of all these different things, whether it’s sexual orientation, gender, [or] immigrants,” said Hasse.

“Education on microaggressions should be very important,” said McQuerry. She and many others who face microaggressions commonly feel that discussion on the concept of microaggressions would be very beneficial.

Onikoro-Arkell stated that “if we pretend that racism is just this huge fundamental thing and we think that it’s almost unattainable like we can’t talk about it, then it seems so much scarier.” However, if we slowly combat broad issues of oppression by addressing all little things such as microaggressions, then it may be easier to attack.