A word to fellow white feminists

March 12, 2014

“No one knows much about feminists when it comes to… people of color,” said senior Halima Aby Munye. Michael Diaz, also a senior, agreed: “The mainstream feminist movement is conducted by middle class white teenage girls.” While this might be an exaggeration, there is some truth to the statement. Every feminist argument I hear at school, that pops up in my Facebook feed, or that I encounter in the news only address issues to the extent that they affect white women.

“White feminism” is the name applied to the exclusive majority of the popular feminist movement, where the voices of white women are incredibly dominant. Not all feminists are “white feminists,” while not all white feminists are proponents of “white feminism.”

As a white woman who is also a feminist, I am speaking from a very privileged standpoint. So are all white women. It is ridiculous for us to assume that we know the problems of all other women when discrimination is more often affected by race and class than it is by gender.

Martha Rampton’s article in PACIFIC, the magazine of Pacific University, explained that “Whereas the first wave of feminism was generally propelled by middle class white women, the second phase drew in women of color and developing nations, seeking sisterhood and solidarity and claiming ‘Womens’ struggle is a class struggle.’”

The problem with characterizing feminism as a ‘class struggle’ is that white women are incredibly privileged compared to women of color. Unfortunately, mainstream white feminism acts as if white womens’ problems are all womens’ problems. The role white privilege played and continues to play in the movement’s development is the source of continuing racial exclusion in feminism.

White women have very little to complain about when we are compared to basically everyone else. The feminist movement is fond of citing the fact that women make less than men. This is true, but only if you amend the statement to read that white women make less than white men.

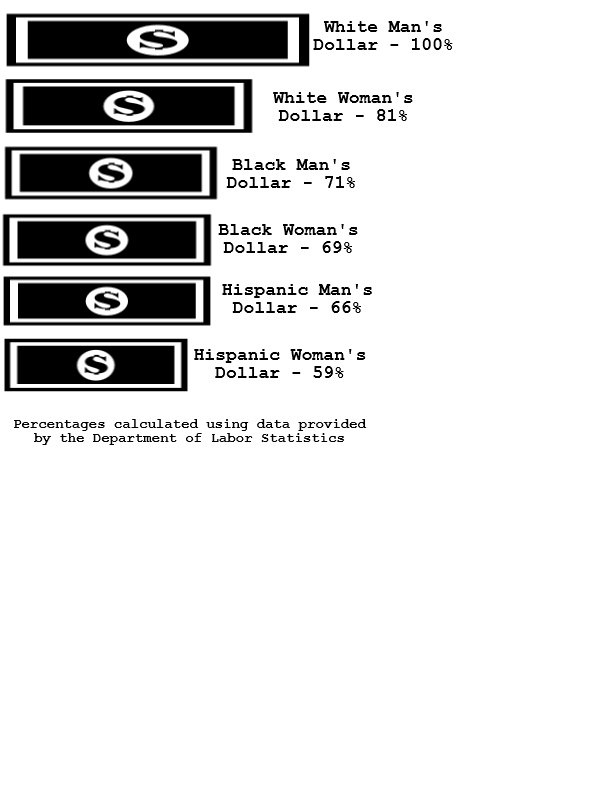

According to 2013 data provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, white women make 81% of the white man’s median weekly income. That is a huge problem. But compared to the Black man’s 71% of the “white man’s dollar,” and the even more astounding 69% made by Black women and the 66% and 59% for Hispanic men and women, respectively, it is pretty clear that white women are more privileged than we fancy ourselves.

In feminist arguments, we only ever hear the percent of that dollar awarded to white women. We are lead to believe that this is the percent made by all women as part of the rallying cry “equal work for equal pay.” This distracts from the much more evident problem of racism in wage distribution. Instead of arguing that we need more, we should step aside and support women of color in gaining rights on par with our own.

Racism within feminism is detrimental to the cause of elevating women’s rights. Popular feminism, the white girl’s feminism, exists within the boundaries of white privilege by holding all women to Western standards. This limits the rights of non-white women. We have a tendency to see ourselves as saviors when imposing our ideas about religion and freedom onto women of different cultures.

A perfect example is Mindy Budgor, the world’s first female Maasai warrior. A white, California transplant on a trip to build a clinic in Kenya, Budgor managed to become a warrior in three months, compared to the customary 15 years. She then came home to write her book about the experience, titled Warrior Princess. Budgor is not only diminishing cultural traditions, but drawing attention away from the attempts of Kenyan women to balance their traditions and efforts toward equality. Kenyan women are already working for equality outside the Maasai warrior tradition.

A more local example is women’s failure to accept beauty beyond Western standards. Senior Priyanka Zylstra gave one example. She asked me to picture a hair care aisle at Target or Walgreens. “There are few products for women with ‘different’ [non-white] hair,” she explained. Instead of addressing blatantly discriminatory beauty standards for women of color, feminism continues to focus on issues faced by white women. Diaz pointed out popular feminism’s focus on dress codes as an example of this.

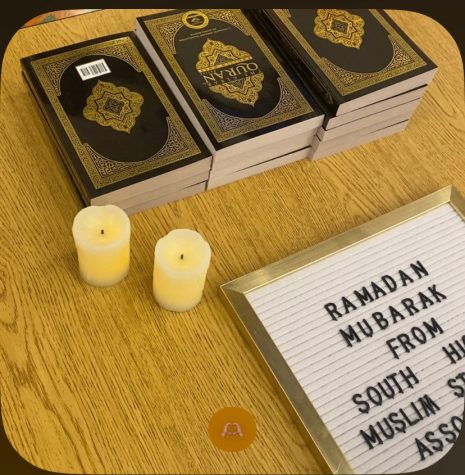

White feminists have a tendency to take offense to claims that other women’s struggles are greater than theirs. Abu Munye experienced this firsthand when a tweet citing feminism’s ignorance, using the popular hashtag “#LifeOfAMuslimFeminist,” drew a lot of negative attention. “I had a lot of people coming at me and calling me names,” she said. White feminists refuse to recognize the exclusivity of their movement.

Denying the exclusivity of the feminist movement is stupid, but doing nothing beyond acknowledging its racism is downright irresponsible. Mia McKenzie of the blog “Black Girl Dangerous” cautioned: “Ignoring your privilege means a whole lot of nothing much if you do nothing to push back against it.”

Maria DiPasquale in Isis Magazine wrote early in February, “Feminism can only succeed with intersectionality. It can only succeed when feminists who are white own up to their privilege, and understand that the position of other women and people with non-traditional gender identities is defined by racism, classism, ableism, and heterosexism, which white middle class women aren’t likely to encounter any time soon.”

While comparatively women of color face greater problems, having that pointed out is a reason to take action instead of offense. White women need to step aside. We cannot pretend to understand other women’s problems, nor can we pretend that our inequalities to white men are comparable to the inequalities women of color face compared with virtually every major demographic group.

Confronting our privilege means not only acknowledging the benefits reaped by the colors of our skin, but relinquishing those benefits. “Pushing back against that power means sharing that power with, or sometimes relinquishing it to, the folks around you who have less privilege and therefore less power,” wrote McKenzie. We also need to just shut up.

“If you can recognize that part of the reason your opinion, your voice, carries so much weight and importance is because you are a white man (or whatever [privilege] is working for you), then pushing back against your privilege often looks like shutting your face,” wrote McKenzie. Our voices are not the only ones that matter. Right now, we should be using our privilege to help women of color get to our level of power and otherwise keeping quiet.