A heartfelt and powerful performance: ‘Motherlanded’ unravels the Chinese adoptee experience

Photo courtesy of Isabel Fajardo

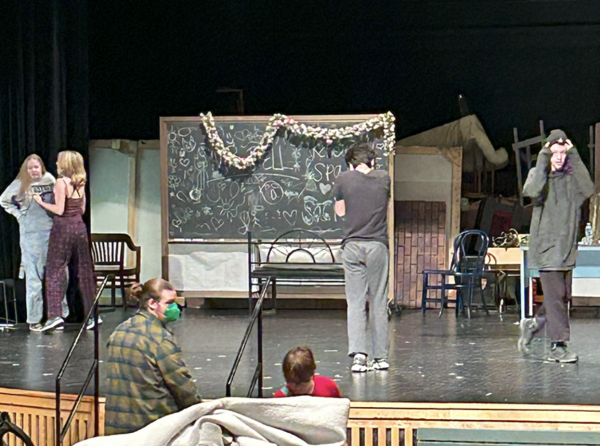

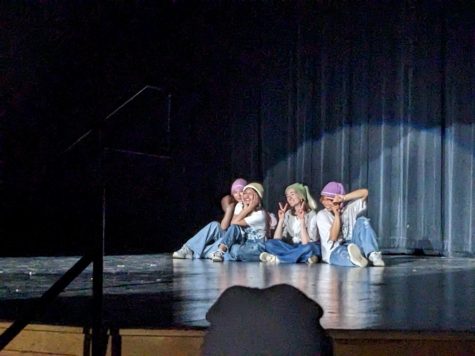

Nearing the end of the show, Julia Gay performs the serene Chinese peacock dance. As she moves and twirls, the dance just feels right: like an acknowledgment of grieving as well as a welcome to growth.

November 8, 2019

A “love letter to Chinese adoptees”: Motherlanded is a moving and thought-provoking show, which will not only leave you teary-eyed, but also with new perspectives and questions.

Motherlanded is a one-woman show written and performed by Julia Gay. It was originally performed in 2016, and was revamped this October at Dreamland Arts theater in Saint Paul. Portrayed through sound, dialogue and movement, the hour-long performance is an autobiography of Gay’s life and experiences as a Chinese adoptee living in America. We get to know Gay throughout all of her life, from the day she was adopted to the present.

Her story isn’t an easy one; Motherlanded talks about the loss and trauma of being a Chinese adoptee, being ripped from one’s people and culture, and taken thousands of miles overseas.

Not being able to speak her native language was one of the biggest losses Gay faced. She spoke about how every other child at her Chinese dance school spoke Chinese except her. As an adult, she asked her mother why she never took language classes when she was younger. Her mother told her that it was an hour’s drive away and therefore wasn’t convenient at the time. The heartbreaking conclusion Gay came to was that she wasn’t able to learn her own language, purely out of a lack of convenience.

Becca Wells, who attended Motherlanded, described in an email what she thought was the most powerful part of the performance: “There was a scene in which Julia was pouring and drinking tea while a recorded dialogue between Julia and her mother played. The conversation was a memory about their trip back to China. Another adoptive family was en route to meet their child’s biological mother, but at the last minute, they changed their minds and asked the van to turn around. Julia was super vulnerable in this scene – both on stage as well as in her conversation with her mother, which was spoken through tears.”

Gay strongly opposes the very concept of white people adopting children of color, despite their good intentions. It was an eye-opening moment for me when she described it like this: white parents adopt children of color to fill a void they have, but they don’t think about the void they’re leaving behind for the children.

Gay is also a stand-up comedian, and sprinkled bits of humor among the intensity of the show. She used a selection of music to play throughout some of the transitions, one of which was Beyonce’s soulful Party. After returning to the stage, Gay addressed the audience. With her mic stand placed upstage, Gay recalled the time she found out what her Chinese name, Li Dang, meant. “Party?” she said joyfully. But then her mother further informed her that “party” referred to the Communist Party. This got some laughs from the eager audience.

In the midst of suffering, there were beautiful moments too. Some of the highlights of the show were when Gay recalled her interactions with two strong Chinese woman as a child.

There was a Chinese restaurant Gay went to with her mother where she was regularly greeted by a middle-aged host. In this scene, Gay acted both as the Chinese woman and as her young self, switching gracefully between the two contrasting characters. For instance, after being seated at a table, young Julia would say “Thanks” in a bright, high-energy tone. Then she would stand up, turn, and her whole demeanor would shift as she became the woman. She would silently wait and then gently bow, using her body expressively.

Another strong Chinese woman in Gay’s life was the head dance teacher at the Chinese dance school attended. She was going to be in a special circus in China, but to get into the circus one was required to hold a handstand for ten minutes. She held it for nine and a half. So she ended up teaching Chinese dance in Ohio instead of achieving her dream.

Gay is a professional dancer and dances with Ananya Dance Theatre. Becca Wells voiced, “I think the true heart and soul of her production was dance – Julia is an extremely talented, beautiful dancer, and that was the most powerful presence I felt she had.”

The show ends with Gay performing the Chinese peacock dance she learned in her childhood, communicating a sense of acceptance. As Gay moves and twirls, the dance just feels right: like an acknowledgment of grieving as well as a welcome to growth.