Gentrification: why your neighborhood may be getting more expensive

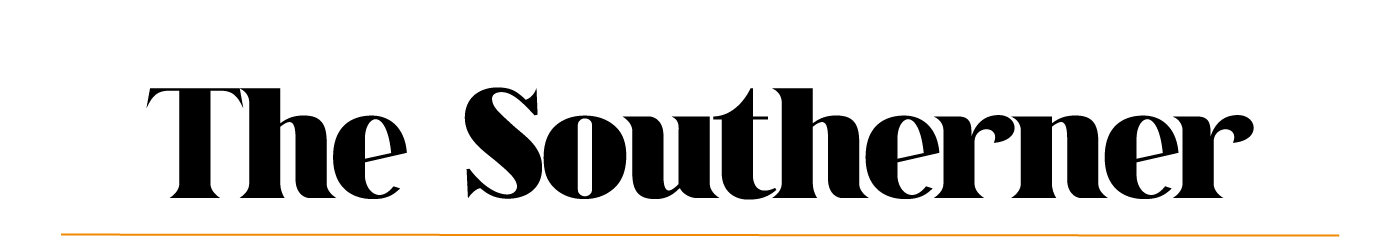

Gentrification occurs when an area is being renovated, wealthier people and businesses are moving in, and rents are rising- and it results in the displacement of many lower income families that cannot pay the higher rates. Many neighborhoods in Minneapolis are undergoing gentrification, including Corcoran: the “Blue Line Flats” apartment buildings are much more expensive than most of the other housing in the area.

Gentrification is a phenomenon in which lower-income residents of a neighborhood are forced to move out because the area is being renovated, wealthier people and businesses are moving in, rents are rising, and people of lower income cannot pay the higher rates. It tends to more heavily impact communities of color because they disproportionately populate historically low-income areas.

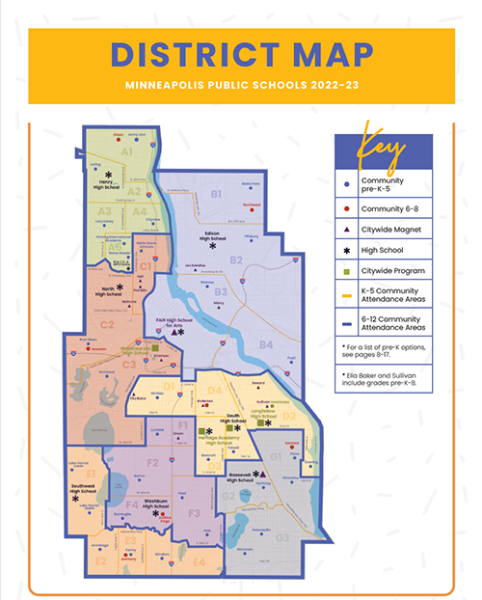

Areas in Minneapolis, including areas close to South such as the Phillips, Corcoran, and Powderhorn neighborhoods, have been undergoing gentrification. A Star Tribune article from November 2016- “Minneapolis is a leader in trend towards gentrification”- cited an analysis of census data done by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland that concluded that Minneapolis has continued to gentrify much faster than many other comparable cities throughout the U.S. also experiencing gentrification, such as Atlanta, Washington D.C., and St. Louis.

Alondra Cano, City Council Member representing Ward 9 (the Phillips and Corcoran neighborhood), summed up gentrification in Minneapolis: “Gentrification has a negative impact on [many] neighborhoods… what’s happening is that through gentrification we’re seeing that the community ecosystem that is built here is slowly changing to displace and push low income communities and communities of color out of the neighborhood.”

In many neighborhoods, rent is quickly outpacing income. According to Cano, “People often ignore the hard truth of our community, which is that people are spending much much more… of their annual income on housing [than they should be spending].”

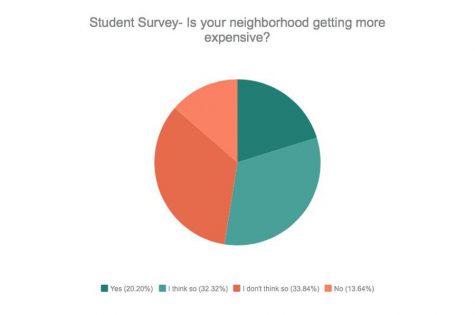

Gentrification affects students at South as well. A survey conducted by the Southerner confirms that 52.5% of students surveyed know or at least think that their neighborhood is getting more expensive.

Freshman “Claire Brooks” who chose to be anonymous for the purpose of this article, shared her story of being affected by gentrification: “[My family] lived in a neighborhood over by Sabathani [Community Center], and they built a co-op across there, and the rents rose and my family did actually have to move to a new spot.”

Brooks continued to say, “We were renting a townhouse… we lived there for many many years, our family had lived there before me and my mom and my brother moved in… the management knew us. Then a new management came in, and they didn’t exactly like us very much….it was just a mix of all those things… we had to move two years ago.”

She added, “A lot of other people living in that area had to move out [too].”

Sophomores Amanuel Desalegn and Ridwaan Abdi have also been affected. They both lived in the East Franklin Buildings in the Seward neighborhood, an area that has shown trends in gentrification more recently.

Abdi’s family moved to the East Franklin buildings when he was very young, having had to leave their previous apartment building in Eden Prairie because of gentrification occurring there. “I lived in Eden Prairie but we had to move because the rent went higher… There was construction… they made new doors to [improve] security… and got new locks.”

For most of their lives, the East Franklin buildings provided great homes for both Desalegn’s and Abdi’s families, but more recently rent rates went up. Desalegn’s family ultimately had to move.

“Right before I left they had construction on our building, we were paying [more] I think for construction so they could make our building [nicer]… but they were doing unnecessary stuff that no one asked for,” Desalegn said. “Me and my mom, we always looked for a house. But when the time came when we [knew] that we had to move… they [had] just raised the rent by a lot, and it was the same amount to [pay] the rent as it was to move into the new house that we were looking at.”

There were also other rising expenses within the apartment building. Desalegn told about programs for kids that would help them stay productive and have fun. “There used to be free programs for kids… [we] did fun stuff, like go on field trips… we would work in the garden… and they made a study buddy type program too… every kid used to be there drawing, using the computers, getting their homework done. And it was always free, especially because they knew a lot of people couldn’t afford it…. [but] now they’re making you pay to do these programs.” Abdi affirmed Desalegn’s experience, saying that now “you have to pay $15 just for a month.”

Councilmember Cano shared several stories that show how gentrification has affected other members of Minneapolis communities, including businesses. “There was a building on Lake and Bloomington owned by a community developer that had a… variety of Latino businesses inside the building, but then another private developer came in and bought the building… and now the private developer has raised rents and doesn’t want to do long term leases with people… he wants to increase the rental prices,” she said. “He has outright rejected to negotiate a lease with [one of] the Latino [businesses]… This is where you see the impact of someone who’s not from the neighborhood who wanted to buy this building but doesn’t have the interest of the community in mind and wants to just see who can give them the best price.”

Cano also told of apartment buildings in the area affected: “we have a landlord here in Corcoran who owns several buildings, and in one of the buildings… [which was primarily] Latino… he… essentially told everyone, ‘you have to leave within the next 3 days because we’re going to upgrade your building and you’re not going to be able to afford to live here in the future,’ yet he didn’t do that to the building across the street which didn’t have any Latino families. The building that was primarily Latino was essentially targeted… the families were forced to leave.”

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, when families are paying more than 30% of their income on housing, they are cost burdened. Census data shows that 42% of families in Minneapolis fall in this category. “[Most] low income families we know [are] paying $900 for one bedroom and their annual income is $24,000… that’s half their income spent on rent every year…. That tells you that this picture is completely off,” said Cano.

Despite how complex these problems are, there are feasible solutions that prove to be very helpful. Cooperative housing (or co-op housing) is when members of a cooperative housing corporation own an entire property together, as opposed to paying for individual units. All members get a say in how the co-op is run and how they will split up the costs to live there. Instead of an apartment building being run by just one person, co-op housing is managed by everyone living there.

The cooperative housing system can be achieved by businesses too, when a building is owned by businesses that all get an equal say in how it is managed. This is called commercial land trust.

Cano shared that, “We have been looking at are expanding the options that the city has for cooperative housing and commercial land trust…homes [and buildings] would never be able to be gentrified because they would be legally bound to an agreement of cooperative wealth building.”

Lastly, she said: “We’re also looking to develop cultural corridors in the city so that we can make sure that these communities are at the forefront of development plans…. so that any developers willing to come in and do business in those ‘gentrifiable’ communities are held accountable to community visions.”

As she begins her second year as Opinions editor and 3rd year on the newspaper staff, Sophia Manolis is more dedicated than ever to make sure new and returning...