Instructions for teachers’ curricula receives mixed reviews

November 24, 2014

Have you ever wondered why your math teacher gives you learning targets, or how a friend who is in the same subject, but has a different teacher, is somehow learning the same thing that you are? The answer is Focused Instruction, which is a collective group of educators that align curriculum under their department by following the state mandated requirements.

This curriculum is what the teachers at South and surrounding Minneapolis public schools are given to create lesson plans for their classes. However this rigid structure doesn’t accurately suit all teaching styles, at least that’s what ninth grade social studies teacher Robert Panning-Miller believes, as a member of the Open program. “[For] anybody who’s working in a team or partnership, Focused Instruction either isn’t happening or the teaming isn’t happening,”, he explained.

The Open program’s structure is almost the polar opposite to the style that Focused Instruction enforces, which creates conflict for teachers who prefer other styles. The structure of the Open Program includes the ninth grade team combining the social studies, language arts, science, and math classes. Along with it’s pairing of language arts and social studies for tenth grade.

Panning-Miller further explained their struggle by saying, “if I follow my Focused Instruction curriculum, and the english teacher and the science teacher do the same, we can’t team [up], we can’t create interdisciplinary thematic lessons, because things don’t match up.”

According to the Minneapolis Public Schools (MPS) website, the instruction will help “develop the necessary tools and systems for Focused Instruction to become necessary practice in every classroom.” MPS also has goals of raising the achievement of all students while also closing the opportunity and achievement gap.

Unlike Panning-Miller, some South educators, like science teacher Mick Hamilton, agree with the methods of Focused Instruction and even take part in it themselves. As a science teacher, Hamilton has found the specific structure designed with other members of the department to be a beneficial tool in running his classes.

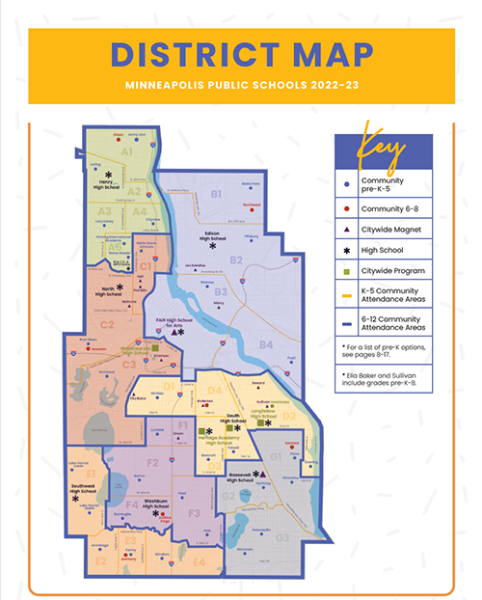

According to Hamilton, his understanding of why South decided to go with this method was “to try to have a more standardized approach across the district, so that if students left here to go to Southwest or left here to go to Roosevelt or any of the other high schools, theoretically they wouldn’t miss out on anything.”

The same goes for switching from classroom to classroom. In theory, if a student changed from Ponto’s biology 1 class to Hamilton’s biology 1 class, there wouldn’t be a problem, because all of the lessons would be structured into the same time frame.

By requiring teachers to follow a structure that states what they need to cover and the time they need to cover it in, the classes under Focused Instruction will follow the same time line of curriculum.

What Focused Instruction does in this aspect, is it structures the framework of a classroom into standards and goal points where teachers of the same subject can meet on common ground. This sets students on a similar timeline in relativity to one another, creating a greater connection between classrooms, and possibly schools.

“For me, when I started here 2 years ago it was nice to have that framework because I’d been teaching at a middle school level for 13 years and so it was nice … to have a framework for where I should be going with my classes,” said Hamilton, regarding the advantages of Focused Instruction. However, he continued with the point that teachers who have been doing what they’re doing for years have a much harder time adjusting to the structure set by Focused Instruction.

Hamilton went on to say, “it’s kind of like cooking … You find a recipe that works, and it might be a little different from what it actually says in the cookbook, but it works. What Focused Instruction is doing is kind of stepping back from that, and going back to the cookbook, saying that you’re supposed to follow this exactly, and I think that’s probably where people are having a harder time [with adjusting].”

This “cookbook,” however, seems more like a single recipe to teachers like Panning-Miller. “It’s a system of standardization of the curriculum. And you’ll hear from district people that it’s not about standardizing curriculum, but the way it is set up, that’s really what it is,” he explained.

The Open program has common conflict with the un-individualized approach to teaching students that Focused Instruction enforces. However, the presence of the instruction doesn’t stop Panning-Miller from structuring his class in an Open program setting. “I have not used Focused Instruction in my classroom … I can’t, if I want to do what we’re doing in Open,” he admitted.

A common issue associated with Focused Instruction is its inability to recognize the partnership developing between departments at South. The social studies and language arts programs are currently working together to collaborate the two courses.

Teachers arrange correspondings units in the two subjects for students to recognize and take advantage of. An example in my own experience from my classes taken in sophomore year was the alignment of the Golden Age in my social studies class, and our reading of “The Great Gatsby” in language arts.

However for science classes, taking from Hamilton’s point of view, the collaboration between the same classes, instead of between classes, is how resources are more easily distributed. “When there’s certain labs that everybody is supposed to try to do, theres ways to have somebody kind of in charge of all of that so they can get us the stuff that we need. Which has really been nice, sometimes the timings not the best but it’s nice to not have to go out and buy plant material, or go out and buy ladybugs or goldfish or whatever it is that we’re using for labs,” explained Hamilton.

Hamilton said, regarding the more unfavored views of FI, “I think teachers like bits and pieces of it, at least in the sciences. I dont know if anybody really likes it 100%…that’s kind of the nature of us as humans, I don’t think anybody really likes anything 100%.”

South’s Focused Instruction program was designed to set a more controlled environment for teachers and their students in the journey to graduating. However, the thought of so little control over their own education was the reason that Avalon student Emma Reilly chose not to attend South.

The action plan at Avalon drew in Reilly when she stumbled upon the school’s open house. What she learned was that instead of having pre-determined lesson structures with built in criteria and instructions, the students are given the necessary state standards on a website called Project Foundry. They can look to see which standards they have and do not have and what they need to do in order to complete the unfilled requirements. This can be done through projects after taking a selected amount of classes in a day.

“Personally, I think that it would apply better to everybody’s way that they learn, because you can make it however you learn and they make it really flexible. But I think also that if you really need that complete structure, then it’s not the right school because you do have a lot of freedom and it can fall out of line,” said Reilly.

Reaching the learning needs of each student is a tall order, and the reason for the creation of programs like Focused Instruction. Unfortunately, this tall order is one that may never be met, unless teachers like those in the Open program are given the tools necessary to teach in their program’s style.

The polarity in opinions from the teachers within South beg the question, how can we create a more cohesive structure that suits every program and class? However, the inability to answer this question is the reason that teachers continuously develop their classrooms, and why programs like Focused Instruction are introduced to our schools.